With asthma disproportionately impacting Bronx youth, state lawmakers from the borough sponsored various bills last year in attempts to help address the issue, but didn’t see much in the way of legislative wins.

Children from the Bronx are disproportionately impacted by asthma, particularly in Hunts Point, Mott Haven, Highbridge and Morrisania, where rates of asthma-related emergency department visits among children were found to be nearly 20 times higher than those in Bayside-Little Neck in Queens, according to a data brief published by the city health department in 2021.

High-poverty neighborhoods where two-thirds or more of the residents are people of color persistently show the highest rates of asthma issues compared with the rest of the city, according to the brief.

On Dec. 23, Hochul signed a bill sponsored by state Sen. Gustavo Rivera and state Assemblymember Karines Reyes that dates back to 2020. The new law requires places that currently provide epinephrine for emergency purposes, such as schools, summer camps, sports facilities and ambulances, to also have rescue inhalers.

But amid the win, various bills fell by the wayside in the Legislature, and two that were successful were vetoed by Hochul: the SIGH Act and the Lydia Soto Law.

SIGH Act

The SIGH Act, which stands for “Schools Impacted by Gross Highways,” would have prohibited new schools from being built within 500 feet of a controlled-access highway, unless the state commissioner of education determines that there is no other site to build a given school because of space limitations.

The bill was sponsored by Bronx Assemblymember Latoya Joyner and state Senator Rachel May, whose district includes the upstate New York Syracuse community adjacent to Interstate 81. After passing through the Legislature, Hochul vetoed it on Dec. 23.

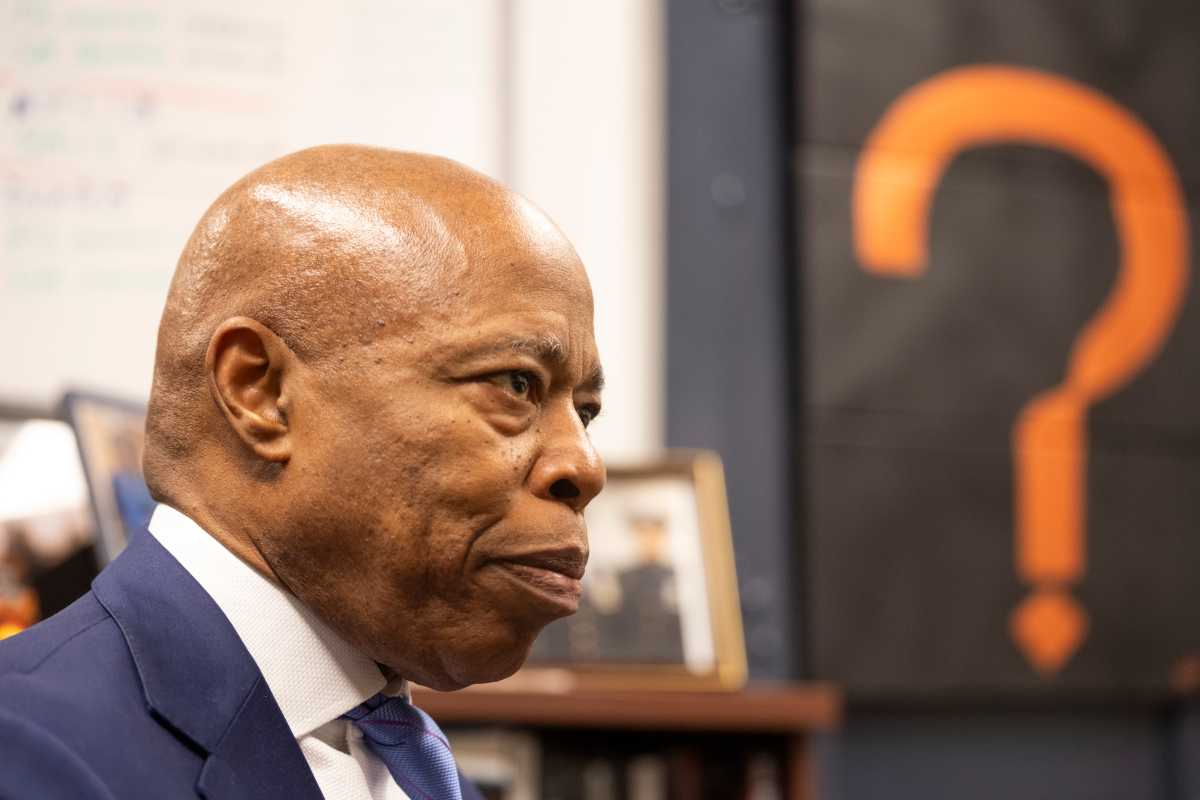

Despite the exception for space limitations, Hochul argued that the bill would limit educational options for students in urban areas without taking other efforts to mitigate pollutants into consideration. She said construction of schools would be “virtually stopped” in some NYC neighborhoods, forcing students to travel further to school outside their communities. She also cited the need for smaller class sizes, which city officials said require flexibility for building new schools. Hochul’s arguments aligned with those from Mayor Eric Adams’ administration.

But Lanessa Owens-Chaplin, the director of the New York Civil Liberties Union’s Environmental Justice Project, who drafted the bill, doesn’t buy their concerns, arguing that 500 feet is just a block and a half in NYC. She said advocates made concessions to cater to the New York City School Construction Authority, such as through the waiver if there aren’t other viable locations to build.

“I would also argue that having a smaller class size when the students are breathing in toxic air is not beneficial to anyone,” she said, pointing to an increase in asthma, cognitive and neurological problems and poor performance that comes from breathing in pollutants.

City officials said that the NYC School Construction Authority evaluates air quality and addresses concerns through school designs, such as with air filters, having small non-opening windows facing the highway, and ensuring play yards, classrooms and entrances do not face the highway. Owens-Chaplin said that while the city can mitigate air pollution, the best option is to build elsewhere.

The Environmental Protection Agency has found that motor vehicle pollutant concentrations tend to have the highest levels within the first 500 feet of a roadway, and points to scientific studies that have found that people who live, work or go to school near major roads are at more risk for short- and long-term health effects, like asthma. The agency’s school siting guidelines, however, recommends considering different factors, including that schools with longer commutes could result in higher exposure overall, compared to a school near a major road with a small commute.

Hochul pointed to other efforts to reduce pollutants, such as a directive for the state DEC to require all new passenger vehicles sold in the state to be zero-emissions by 2035, but Owens-Chaplin argued that students will go through their entire academic careers before then.

Lydia Soto Law

Named after a child from the South Bronx who died of asthma complications, the Lydia Soto Law sought to create a council within the state’s Health Department to assess the asthma risk factors for minorities in the state, as Black and Hispanic children are disproportionately impacted by lung disease. The council would identify barriers to quality asthma treatment among minorities and develop a plan to address these issues, as well as facilitate an asthma awareness campaign.

Hochul vetoed the bill on Nov. 23 following passage through the state Legislature. The rejection came along with 38 other bills that would create studies or commissions, with the governor saying the initiatives would be better suited for the state budget process because of their fiscal impacts.

The bill was sponsored by Reyes in the Assembly and now former state Sen. Alessandria Biaggi in the state Senate. Reyes, who said she was asked to carry the bill by Biaggi, said the bill’s rejection was “heartbreaking” and called the budget reasoning an “excuse.”

Biaggi could not be reached by press time.

At least five other bills sponsored by Bronx lawmakers relating to asthma didn’t make it through the state Legislature in 2022, though two involved ideas with similarities to the Lydia Soto Law.

Reach Aliya Schneider at aschneider@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4597. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes