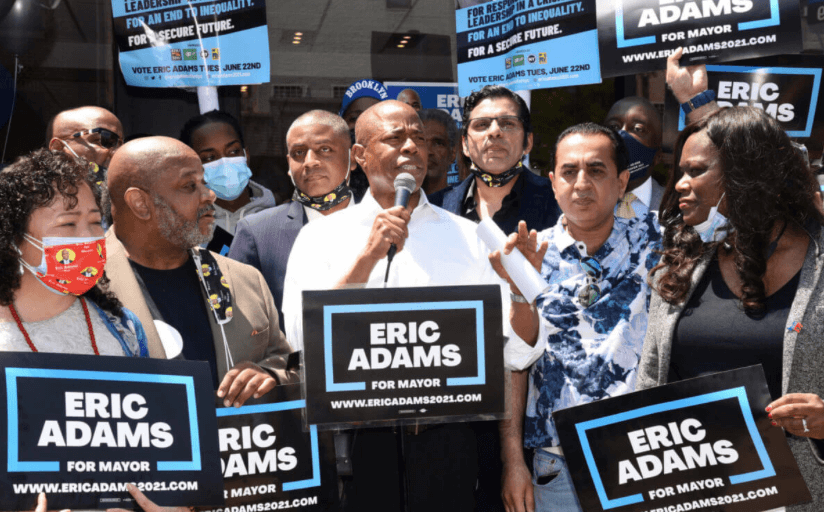

With Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams almost certainly becoming New York’s next mayor in January, real estate developers and community advocates alike are rushing to understand the future of land use policies under the city’s self-described “complex” next chief executive.

While Gotham deals with a severe housing shortage, and ranks as the most expensive city in America, Adams will assume broad powers over the development industry — including the power to sign off, or veto, every rezoning request across the Five Boroughs.

When developers purchase land, and wish to build higher than current zoning laws allow, they will seek a rezoning through the lengthy Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, which requires a certain percentage of housing units be designated as “affordable” — and needs approval by the City Council, the City Planning Commission, and City Hall.

Current Mayor Bill de Blasio had planned to build around 300,000 affordable units by 2026, which would require significant amounts of upzoning, and would be aided by the neighborhood-wide rezoning of Gowanus, which alone would bring some 3,000 below-market-rate units.

Adams, on his campaign website, vowed to upzone “wealthier areas where we can build far more affordable units,” which comes in contrast to the trend of only allowing land use changes in poor, predominantly non-white neighborhoods like East New York and Inwood. As a candidate, Adams found most of his votes in the outer boroughs, and less affluent neighborhoods, possibly giving him license to ignore the protests of residents in ritzier areas like SoHo, which is currently under consideration to be rezoned, despite fierce opposition from locals.

The almost-certainly-next-mayor also pledged to convert office buildings to apartments, and legalize basement apartments and single room occupancy units.

It’s complicated.

Adams has a friendly relationship with the real estate industry. The beep did not eschew donations from them during his mayoral run, even as many other candidates did, and is reported to have courted them aggressively.

As Brooklyn’s borough president since 2014, Adams has offered advisory rulings on land use changes in Brooklyn as parts of the borough rapidly gentrified and a number of large developments went through the ULURP process — offering observers a glimpse into his possible feelings on zoning changes.

An examination of some of his past rulings, though, would seem to run contrary to his pro-development-in-rich-areas mantra, according to some advocates for more housing.

“I think rhetorically, he is pro-development,” said Will Thomas of the development-boosting group Open New York. “But in the same way that Bloomberg was seen as pro-development, and Bloomberg down-zoned a large portion of the city.”

Borough Hall has backed the down-scaling of residential buildings in a number of recent projects to come before them, most recently with the 840 Atlantic Avenue rezoning. In that project, Adams sided with Community Board 8 against developer Simon Duschinsky by demanding a less dense residential building than the one currently pitched by the developer, which would see an 18-story tower replace a drive-through McDonald’s on an undeveloped corridor in hyper-gentrified Prospect Heights. The less dense version of the development favored by the beep and the community board will ultimately contain fewer units of affordable housing than currently proposed.

His office similarly sided with residents in the wealthy enclave of Vinegar Hill whorejected a proposal for a eight-story apartment building on Front Street in favor of a less dense alternative. While the original zoning requested by the developer would have allowed for five to seven units of income-targeted housing, the version preferred by the borough president and Community Board 2 contained none. The developer eventually pulled its proposal and the site remains a parking lot for trucks.

These examples share a common theme of Adams siding with members of community boards, whose members are appointed by Borough Hall. While community boards, like the borough president, offer only advisory opinions, their elected officials more often than not follow their leads.

“Community boards have the first say in the ULURP process, even though it’s informal and non-binding,” said Thomas. “There’s a lot of status-quo bias and I think that filters into City Council and borough president decisions.”

Power in his people

Preservationist groups concede that Adams is undoubtedly a pro-real estate figure, but say that his record of siding with community boards in down-scaling is largely a product of the Borough Hall land use staff, who attend public meetings and coordinate with community board members.

“His Brooklyn borough staff are smart and knowledgeable, which is too rare in elected official offices, and were many times responsive and have crafted nuanced ULURP recommendations that have reflected local voices, even if they did not control overall policy,” said Linda Trujilla of the preservationist group Respect Brooklyn.

Trujilla said the group is hopeful that if some of his land-use staff follow him to City Hall, they will bring an emphasis on community-oriented planning for development.

“If some of the Adams team continue on, they will be helpful in the push for public investment in housing, community land trust models, needed landmarking and preserving green space and creating more gardens and parks as long as the various progressive political movements and unions stay cohesive and unified and work across substantial issues and not woke gestures,” she said.

All told, Adams’ stance on development is somewhat of an enigma.

While his advisory opinions as borough president may have been guided by political calculations, it remains an open question whether his decisions as the city’s top executive will be guided by similar concerns.

But now, in post-pandemic New York, rents are once again rising, and visions of a lower-cost metropolis, propelled by a residential exodus, appears to be a lost hope for renters, leaving land use changes as the only hope of many for cheaper living costs.

Building enough apartment units to make a significant dent in prices would ruffle many feathers, but Adams has pledged to do so, and his electoral constituency may give him the leeway to do exactly that. But all anyone can do now is wait, while the candidate prepares to leave his mark as the 110th mayor of New York City.

This article appears courtesy of our sister publication Brooklyn Paper.