As New York lawmakers debate implementing a “bell to bell” cell phone ban in schools, some campuses have already embraced the policy — and say they’re seeing positive results.

At Advanced Math and Science II (AMS II) and Humanities II (HUM II) in the South Bronx — part of the United Charter High Schools network, which serves nearly 3,000 students across the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens — a full-day phone ban has been successfully implemented with the help of technology and strong support from parents, teachers, and students.

The implementation of their policy has proved timely. A fall 2023 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 72% of high school teachers identified student phone use as a major classroom distraction. Research has also linked excessive social media use to depression, anxiety, loneliness, and suicidal ideation.

Dr. Curtis Palmore, CEO of United Charter High Schools, said all seven of the network’s schools have adopted bell-to-bell bans — and he hopes the entire state will eventually do the same.

Even letting students use their phones during lunch or other non-instructional periods doesn’t serve them well, Palmore noted in a recent op-ed.

“We need to create environments during the school day, but outside of the classroom, in which students can communicate interpersonally, without screens, to prepare them for success in college, careers, and their social lives,” he said. “If we are serious about improving student learning and well-being, we must stand firm on this.”

Behind the ban

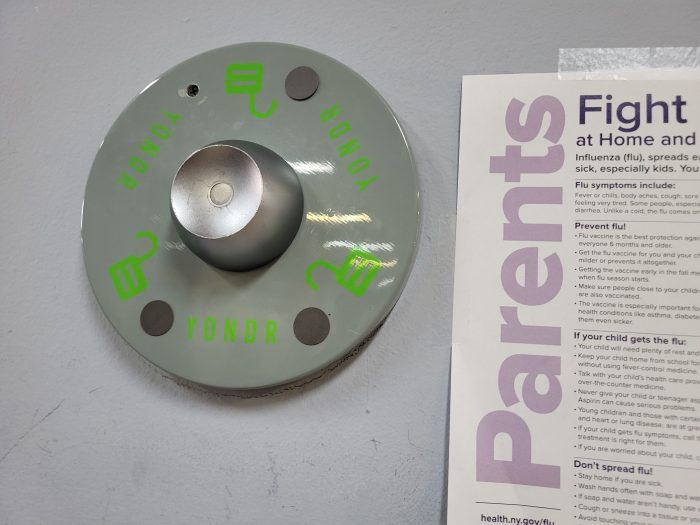

At AMS II and HUM II, students are required to use Yondr pouches to secure their phones during the school day.

Each student receives a personal pouch equipped with a magnetic lock. Upon arriving at school, they place their phone inside the pouch and tap it against a wall-mounted device, which locks it. While students keep the pouch with them throughout the day, it remains sealed until dismissal, when they unlock it using the same wall device.

At AMS II—a high school of 485 students where Principal Sandy Manessis has served since 2012—the cell phone policy has been in effect for the past two years.

Manessis said the idea took some getting used to, but now, “It is still one of the most popular decisions I have made as a school leader.”

Prior to the ban, some teachers used cell phones as an instructional tool but struggled to keep kids from using them for non-learning purposes, Manessis said.

The problem came to a head following the pandemic. Manessis said kids were often seen scrolling mindlessly during class and, perhaps more disturbingly, barely interacting with each other. Most agreed, she noted, that something needed to be done.

She convened teams of administrators, staff and teachers to work together on what a potential phone ban might look like and examine the impacts of excessive screen time.

The policy was a collaborative effort, said Manessis. For such a major change, “Buy-in is number one.”

Once the phone ban was ready for rollout, the school piloted it in small summer programs, and school officials met with families over the summer to explain the change and reasoning behind it.

At first, many students were not fans, said Manessis.

“Yes, they huffed, puffed, they rolled their eyes, but they knew … that we were going to follow up,” she said.

As for parents, only two complained, and most loved the idea, said Manessis. Parents started fully cooperating if their kids were caught without their Yondr pouch during random checks, and some even said they wanted to use the pouches at home.

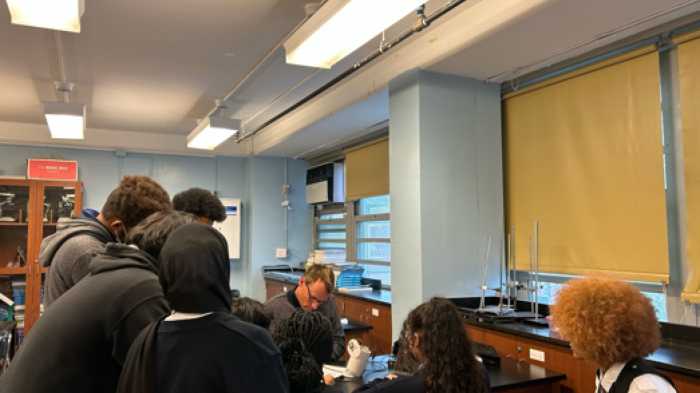

After the ban was in place, teachers saw an immediate difference, where it was “night and day in student engagement,” said Manessis.

The phone ban has also had positive social impacts. Manessis said the cafeteria used to be strangely quiet, with students’ eyes glued to their phones. Within a week after the ban, she passed by to see them having a dance party.

“To see kids being kids again is so powerful,” she said.

Part of the routine

Manessis said that while kids are “always one step ahead of us” and sometimes try to sneak phones in or use a laptop for non-learning purposes, the administration sees only three to five violations per month.

“We’re not giving up on the challenge or the battle,” she said.

Steven Rodriguez, associate director of school culture at AMS II, said that many students now admit that cell phones in school were a big problem. Now, “they fake-complain” about the ban but are fully accustomed to locking and unlocking the Yondr pouch each day, he said.

Yessenia Crespo, a health teacher upstairs at HUM II, agreed. “It’s routine,” she said.

Crespo said the school was previously located in a campus with metal detectors, which made it impossible for kids to bring phones in unnoticed. But when HUM II moved to the Jane Addams campus, which has no detectors, staff tried collecting students’ phones and found that tactic frustrating and unsuccessful.

After seeing kids constantly distracted from learning and beefing with each other on social media, teachers petitioned to bring back a cell phone ban, Crespo said. So HUM II began using Yondr pouches midway through last school year.

She said using the pouches, rather than having staff try to confiscate phones, is great for students’ self-management and accountability. “Now it’s putting the control in their hands.”

Sharon Hernandez, parent of a senior and school attendance coordinator for AMS II, said that the policy is so ingrained that even if a student forgets their Yondr pouch, they turn their phone over to the office.

“They already have that culture in place to turn it in to an adult,” she said.

Hernandez said her son used to be “very antisocial,” which she feared would become a bigger problem after two years of remote learning. But without the distraction of phones in school, he has developed great relationships with peers and staff, she said. She called the cell phone ban “one of the best things ever as a parent.”

‘Live in the moment’

Students at AMS II and HUM II said while they wish phones could be used in moderation, the bans have made their schools better overall.

At HUM II, the new policy took effect halfway through last year, which was a change for students such as Brihanna, a sophomore, and Brian, a junior. Both said they avoided using their phones during class prior to the ban, but it was still an adjustment.

School safety — not social media, games or texting — was their first concern when they found out about the ban, both students said.

Brihanna said she worried about not having the opportunity to text her mom if something bad happened during the school day.

If there was a serious lockdown “and I can’t even text my mom goodbye … it’s a scenario that plays in my head,” she said.

Brian said he also worries about having his phone locked up if an emergency strikes. “That’s something that scares me sometimes.”

But George Ashun, senior at AMS II, said he saw nearly every aspect of his high school experience improve after the cell phone ban.

Ashun said prior to the policy, many students used their phones to “disassociate from what’s really going on around them.”

When news of the all-day phone ban came down, “I was annoyed at first, but it turned out to be something I didn’t really mind after the first week.”

Ashun said without his phone, he “had no choice” but to concentrate more in class, and his grades improved from the low 80s to mostly 90s and 95s.

He said the ban has also had a positive effect on students’ social lives, which is especially meaningful in their senior year.

“A lot of people I didn’t think would get off their phones … found their groups and type of people they want to be around,” said Ashun. He said his group of friends go to the gym together, play sports and try out different restaurants.

The cell phone ban “made it so that you have to be more in the moment,” he said. “Time is the one thing you can’t get back, so why are you spending all of it on your phone?”

Power of the people

In recent years, schools in 41 states have spent over $2.5 million on Yondr pouches.

But schools aren’t the only places using them. Some concert performers use them to prohibit audience members from taking photos and videos, and some jobs, especially those involving sensitive information, require employees to lock up their personal devices, said HUM II Principal David Neagley.

Every change involves a trade-off, he said. Phones can be a useful learning tool, but “how do we balance this when they’re addictive?”

It was “a long journey” to the current policy, developed with ongoing student and staff input, he said. Ultimately, when it comes to improving kids’ learning and well-being, everyone must play a role and not think of one policy as the magic bullet.

“The phone ban itself is a really positive thing for school culture, but not the ban that’s gonna solve it,” said Neagley. “It’s the people of this community and the organization that’s gonna make this come to light.”

Reach Emily Swanson at eswanson@schnepsmedia.com or (646) 717-0015. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes