Doctors had been monitoring Janel Aikins-Addo’s pregnancy regularly into her second trimester.

Already deemed high risk from issues with previous pregnancies, the Bronx mom of two — soon to be three — kept up with routine prenatal visits. But this past February, after she was hospitalized with gestational complications, Aikins-Addo lost her baby nearly seven months into her pregnancy.

“I think we were mostly sad about the expectations that we had for her,” she told the Bronx Times. “We know she’s with God, we’re not too sad about that. We would like her to be here with us, but we’re not sad about that.”

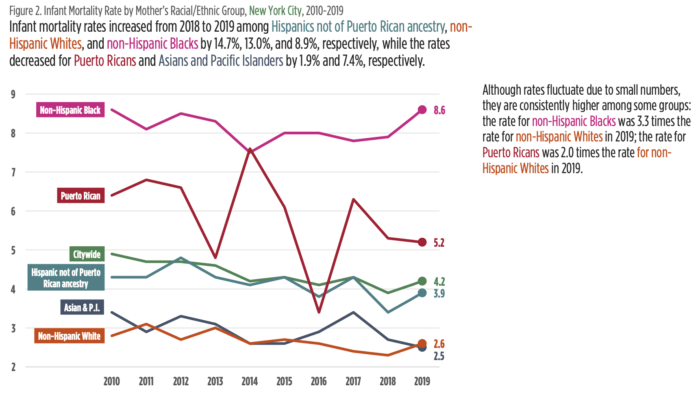

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the infant mortality rate in 2019 — referring to the number of babies who die before their first birthday — was 3.9 out of every 1,000 live births in New York state. New York City’s rate was higher that same year — at 4.2 per 1,000 — which also represented a 7.7% increase from 2018, according to the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

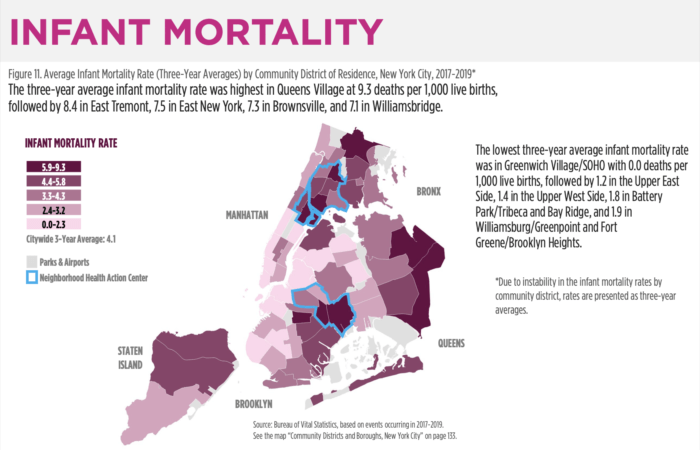

This is of particular concern in Bronx County — which had the highest infant mortality rate across the five boroughs from 2017 to 2019 according to the health department — where five out every 1,000 live births ends in death. Staten Island in Richmond County follows at 4.9, then Queens County and Brooklyn in Kings County at 3.8. Manhattan in New York County has the lowest infant mortality rate — 2.9 per 1,000.

Because of the high rates in the Bronx, a local organization will be hosting an awareness walk between 9:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. at Walter Galdwin Park in East Tremont on Wednesday.

Alma Idehen is a director of the Department of Family and Social Medicine Bronx Healthy Start Partnership at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. She is one of the organizers of the fourth annual Strollin’ in the Park Infant Mortality Awareness event on Wednesday, where there will be baby safety demonstrations, educational materials and representatives from the medical community.

Idehen said infant mortality in the Bronx is not a walk in the park like the event is, and that the phenomenon impacts not only the families who have lost a child, but also society as a whole.

“If we don’t really stop and understand what are some of the causes or the reasons, then we are going down a slippery slope consciously and deliberately,” she said.

The East Tremont and Williamsbridge areas in the Bronx are two out of the top five neighborhoods with the highest infant mortality rates across the city. According to the health department, the rate in East Tremont was 7.5 per 1,000 from 2017 to 2019, followed by 7.1 per 1,000 in Williamsbridge. Other neighborhoods with high infant mortality rates out of 1,000 live births included Queens Village, Queens at 9.3, East New York, Brooklyn at 7.3, and Brownsville, Brooklyn at 7.3.

Idehen said these statistics put the Bronx at risk for losing its population. She said the numbers are especially jarring among women and babies of color — particularly those in the Black community.

According to the health department, from 2017 to 2019 the infant mortality rate for Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander babies in the Bronx was 3.3 per 1,000 live births. For white babies that was up only slightly, at 3.8. But the Black community saw their numbers nearly double — to 7.4 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Idehen said a history of social oppression and health inequity likely explain the stark disparity in mortality rates among the Black population.

“There are so many things (the Black population) is grappling with, just on a survival basis,” she said. “You find these disparities widening because these families are dealing really at a very difficult point in managing all the things that they need to manage.”

In addition, access to prenatal care and health insurance, safe housing, sufficient food and education all play a role in infant mortality, Idehen said.

“There are real societal factors that if we know and understand we can try to figure out how do we address them, before these emergency situations come into play,” she added.

Dr. Nereida Correa, an OB-GYN who has been practicing in the Bronx for 35 years, said the tricky thing about infant mortality is that the medical community is not always sure what causes adverse outcomes.

“Pregnancy is a happy time but it’s also a very dangerous time for the woman,” she said.

While hypertension — which is high blood pressure — diabetes, obesity, diet, stress, prematurity and low birth weight are considered some of the primary factors, every case of infant mortality is unique. Add to that list racism and discrimination, Correa said, and it could explain why families of color, especially Black families, are losing more pregnancies and babies than their white counterparts.

“We really don’t know the exact causes of it,” Correa said. “We know some factors contribute to it, such as stress, and in the case of Black women, maybe the amount of racism that they have been exposed to in life.”

Suffocation, which can also cause sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS, is one of the most common causes of death in infants that Correa hears about. In some cases, she said, parents or family members have accidentally rolled over on top of their babies or let them fall underneath too many blankets or pillows while sleeping with them on a couch or a bed. Babies are also at risk for suffocation when they have too many extraneous objects in their cribs, like blankets or plush toys.

While the statistics on infant mortality look bleak, Correa said there are resources in the Bronx for families and pregnant people, including free health centers for under or uninsured patients, public hospitals and prenatal education classes.

Correa also said she and others have been working toward integrating the national Fetal and Infant Mortality Review program into Bronx-based medicine. The program aims to equip communities across the country to prevent infant deaths through in-depth case study review.

“We’re not just reviewing for academic (purposes),” Correa said. “I think we’re reviewing to make sure that we are able to find out why and look at ways that we can prevent. So the prevention, I think, is the biggest goal.”

Aikins-Addo, who lost her baby in February at 27 weeks, said her doctors never found out what exactly went wrong.

She had a history of preeclampsia — a complication in pregnancy that may result in high blood pressure and other organ damage — and other cervical issues, which proved difficult in the past. Aikins-Addo delivered two babies prematurely, had a miscarriage in 2017, and lost another baby after four months of pregnancy in 2020.

“To actually have your baby and see your baby and hold your baby and they’re not alive, that was very, very, very traumatic,” Aikins-Addo said.

The Bronx native said her family’s faith has helped her through the loss of her baby in February. Aikins-Addo said her sons —ages 10 and 7 — know their little sister is an angel now.

There might have been a different outcome for her family, Aikins-Addo said, if doctors had continued to monitor her regularly during her pregnancy. She said pregnant patients, especially those patients of color, have to be able to ask questions about their health care.

“Don’t be afraid to advocate for yourself,” Aikins-Addo said. “I just wish that the health care system would take women — especially Black women — take our concerns seriously, our pain seriously, and really hear us.”

For more information on the Bronx Healthy Start Partnership, visit the Albert Einstein College of Medicine webpage.

Reach Camille Botello at cbotello@schnepsmedia.com. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes