In the first week of school this year, indoor classroom temperatures reached nearly 100 degrees in parts of New York.

Kids were sluggish, irritated and dripping in sweat. They reported headaches, nausea and some students required trips to nurses’ offices. Teachers and school staff desperately tried fans, opening windows and closing curtains all while battling their own heat exhaustion after spending hours in the same sauna-like conditions.

Since the beginning of September, more than 600 educators have shared stories of extreme heat, describing classrooms that lacked effective climate control systems as “heartbreaking,” “inhumane” and “a living hell” during what should have been the energizing start to a new school year.

As parents, teachers and elected representatives in our communities, we have seen how budget battles have forced difficult choices when it comes to facility upgrades. For years, many of our schools have not had the resources to create the learning environments that all of our children deserve.

But safe temperatures are not a luxury item to be considered only if there are funds left over. The combination of aging school infrastructure, rising temperatures from climate change, and worsening air quality has heightened the effects of hot classroom conditions on our educators and children. We must take action as a state to ensure students and teachers are spending their days in safe and healthy spaces where they can thrive.

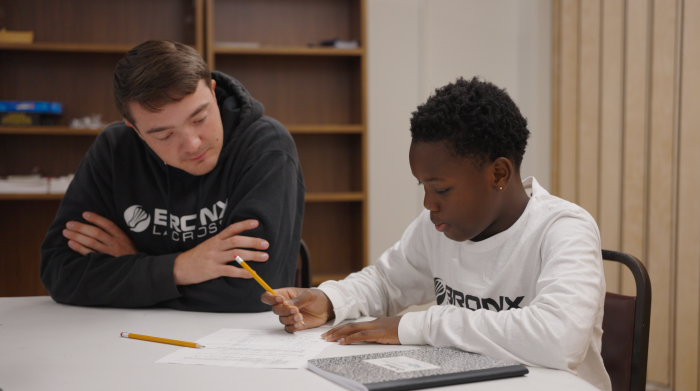

We know that prolonged heat exposure directly affects mental, physical and emotional wellness, so it should be no surprise these conditions halt learning and growth.

A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper Heat and Learning concluded that every 1-degree increase in school-year temperature leads to a 1% learning loss.

The impacts are up to three times as damaging for students who are Black, Hispanic or living in poverty, the paper’s authors said, and they proposed that long-term effects of regular heat exposure on a nation’s children could even pose a threat to its economic growth.

Oppressive heat also impacts social and emotional skills that are key to healthy schools. A 2023 study through Harvard University found that extreme temperatures exacerbate student disciplinary referrals, an effect the author found was “driven entirely” by lack of air conditioning.

Both within the U.S. and internationally, a study published in the Nature Human Behavior journal in 2020 found that most students scored increasingly worse on exams each school day where the temperature rose above 80 degrees. Temperature policies aimed at improving physical learning environments would improve both student cognition as well as teacher retention and “may pay larger dividends over time than was previously appreciated,” the researchers concluded.

But very few districts follow consistent policy standards, even though classroom heat is a growing problem across the nation. According a June 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office, an estimated 41% of public school districts need to replace or update their heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems in at least half of their facilities, representing about 36,000 schools.

In New York, when combined with other environmental factors, such as air quality warnings caused by wildfires in Canada this summer, there have been days when classrooms and school facilities have been intolerable. But, even though the state has established minimum temperature requirements for its classrooms, there are no standards for protecting children, teachers and school staff during extended periods of prolonged heat exposure.

The Safe Temperatures for Schools Act in the state Legislature would change this. It establishes a maximum temperature of 88 degrees. Any higher temperature would require that students and staff be removed from the overheated classroom, cafeteria or support service area.

It also would define any day where the temperature reaches 82 degrees indoors as an extreme heat condition day that would mandate additional safety precautions and cooling actions.

The idea isn’t new at all. In 2021,, the White House said that workplaces should emphasize safety monitoring once the heat index hits 80 degrees. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has recommended that employers keep office thermostats between 68 and 78 degrees, and have maximum temperature requirements of 85 degrees.

It is unacceptable that we are not giving our children, teachers and school staff the same level of consideration when we are asking them to engage in dynamic and collaborative learning environments.

The facts are clear that extreme heat is a real danger to our children and educators. They should not spend their days dreaming of ways to survive the sweltering temperatures. It’s time we set clear, statewide heat standards to make sure our classrooms are healthy spaces where the focus can be on teaching and learning.

Melinda Person is the president of New York State United Teachers. Kyle Belokopitsky is the executive director for New York Congress of Parents and Teachers. James Skoufis is a state senator representing the 42nd District. And Latoya Joyner is a state assembly member representing the 77th District.

For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes